Bureaucracy is Hell

Bureaucracy is as old as civilization, but it may have gotten its start in a much older place: Hell. On the occasion of Piermont & Thorne’s Demon in a Box Collection, we explore the hierarchies of the Underworld and offer a reason why bureaucracy might not always be a bad thing.

The Spanish Franciscan Alphonsus de Spina (1410-1491) claimed no fewer than ten varieties of demons.

His list included the fates, incubi, succubi, nightmare demons, poltergeists, and the marching hosts, “which appear like hordes of men making much tumult.” Other demonologists created their own organizational systems, with little consistency among them other than an acknowledgement that demons are as numerous as any other species. Infernal taxonomy reached its apotheosis/nadir in 1612, when Father Sebastien Michaelis published his Histoire admirable de la possession et conversion d'une penitente, a list of major and minor demons alongside their name, rank, and purview.

Lot 30: The “Corrupted Monk” Box, whose image of the Shaolin monk Xuětíng Fúyù was altered by the Box’s imprisoned demon, a ferocious Taotie.

As recently as 1947, the Catholic Church’s Rituale Romanum required its exorcists to demand the name and rank of the possessing demon. During a 1618 exorcism in Auch, France, a demon who had possessed an eleven-year-old boy gave his information as “Mahonin, of the third hierarchy, and the second order of archangels, and that his living, before he entered the body of the possessed, was in the water.”

Michaelis’ taxonomy is still referenced among scholars today and finds relevance in certain cursed artifacts. The 16th Century “Widow’s Tear” miniature gold bottle (lot no. 17 in our DiaB Collection) is listed in the Histoire admirable as containing the First Hierarchy demon Sonneillon, fourth in the order of the Thrones, who “tempts men with hatred against their enemies.”

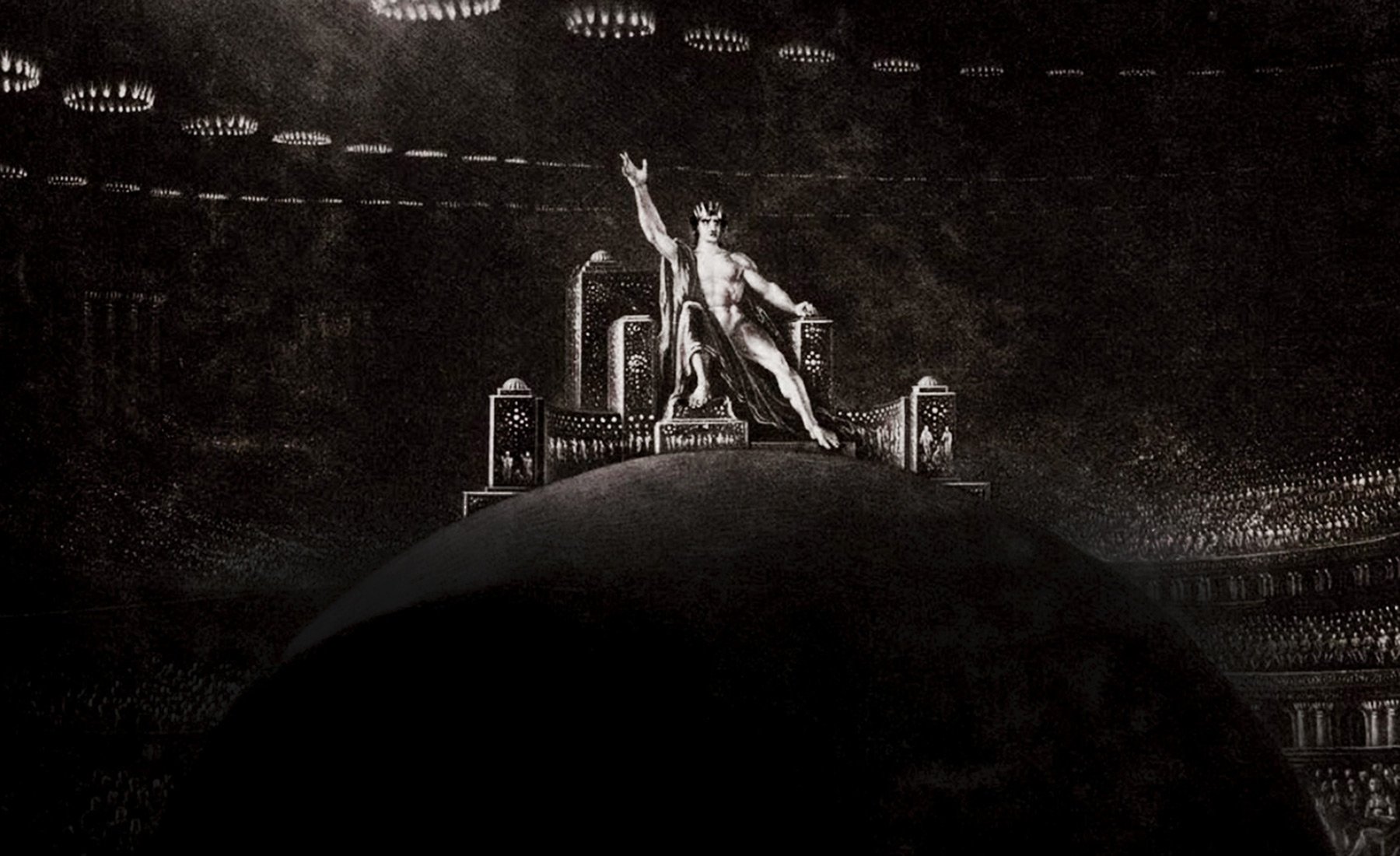

Lot 14: This early 17th-century reliquary features an original painting by Jusepe de Ribera, titled The Mathematician Collects their Ballots. We see what may be Pythagoras in Hell, surrounded by demons who are voting on some matter. Note the shadowy “nightmare demons” on the front panel, and on the side panel on the far right top row, we see the grinning visage of what appears to be the demonic Marquis Fortas.

Demonic hierarchies are not limited to Christian sects; the demon Mara in Buddhism is equivalent to Satan in Christian theology, and ranking below Mara are many evil spirits including Asuras, Yakshas, and Rakshasas. The “Corrupted Monk” Box (lot no. 30) supposedly holds a Taotie, one of Buddhism’s “four evil creatures of the world.” So powerful is the corrupting influence of the Taotie that it slowly transformed what was an elegant portrayal of the famous Shaolin monk Xuětíng Fúyù into a portrait of a cracked, withering man. According to legend, when the gingko tree pictured on the Box rots to a stump, the Taotie will escape.

The bureaucracy of Hell is most evident in Judeo-Christian demonic hierarchies, from middle-management devils to entry-level fiends hoping their malevolence earns a promotion. A trapped demon has many reasons for its fury beyond the tedium of imprisonment and the humiliation of being captured by a lowly mortal: every moment spent in confinement is a lost opportunity for career advancement. The 16th-century theologian Paolo Barbo told the story of an ambitious demon called Iuvart who spent one thousand years trapped in a mirror as his colleagues improved their standing in Beelzebub’s court. Barbo claims Iuvart’s eventual escape led to the deadly (and still unidentified) “Sweating Sickness” epidemic that killed thousands throughout England in the 1500s.

Lot 27: The mid-20th century “Devil in an Icebox” fiberglass coffer, supposedly containing a demon so powerful that the acronym “INRI” is needed to keep it imprisoned.

Lot 17: 16th-century Japanese "Widow's Tear" miniature gold bottle, allegedly containing the powerful demon Sonneillion.

Ironically, bureaucracy might be the one of the few forces powerful enough to hold the legions at bay. Hell’s labyrinthine systems of governance slow the passage of major initiatives, frustrating even the most powerful demons. Francis Barrett in his 1801 book Magus or Celestial Intelligence tells of gossip “gleaned from an imp of the most pathetic kind,” who reported that “Leviathan, next only unto Lucifer, is often buried in paperwork of such volume that it reaches to the top of his throne room and causes endless vexation.”

However accurate the imp’s—or Francis Barret’s—account, bureaucracy’s effects lend fresh meaning to the quote from the Emerald Tablet, the definitive Hermetic text of the Middle Ages: Quod est superius est sicut quod inferius, et quod inferius est sicut quod est superius.

“That which is above is like to that which is below, and that which is below is like to that which is above.”

To see more items in Piermont & Thorne’s Demon in a Box Collection, visit our auction page.

The authors credit Rossell Hope Robbins’ Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology for much of the information provided.

Notes/Additional Readings:

Numbers vary widely but most demonologists agree that Hell is packed, and not necessarily with sinful humans. Alphonsus de Spina posited one-third of original angels became devils, numbering 133,306,668, which puts the population of original angels at an astonishing 399,920,004.

Father Michaelis was vice-inquisitor of Avignon and responsible for the torture and murder of dozens of innocents. For an in-depth analysis of whether or not this calls his scholarship into question, see Jonathan L. Pearl’s The Crime of Crimes: Demonology and Politics in France, 1560-620. Wilfrid Laurier University Press, 1999.